Reflecting on Change

Few words have recently been used as ambiguously and non-specifically as the word “change.” Digitalization, customer behavior, threats of disruptive startups, COVID-19 impact, ecological and social responsibility requirements – all these developments seem to push companies, their management and their employees “to change.” Especially in the last decade, which was strongly shaped by digitalization, the call for change agents has become loud. The market followed: LinkedIn now lists more than 150,000 people with the title “Change Agent” or “Change Manager”.

Our daily business at Excubate involves change either as part of an internal digital transformation endeavor within our client’s organization; or, change management is needed to enable the more externally oriented building of a new venture. Based on that experience, we have developed a well-defined view on how change works and how an “agent” can or cannot drive it.

The take-away: As soon as someone carries the title ”change agent”, advertising “change” as their main professional activity, they can hardly act as an effective change agent. Some may find this thesis provoking, so let’s get to why we believe it’s true.

Change is not achieved by teaching: The information-action fallacy

Most business people have had an epiphany during the COVID-19 crisis: Switching from personal meetings to online meetings actually is possible and even the most tech-unsavvy people eventually managed. Why? Because they were required to. Required to log into MS Teams, switch on their camera and play with the mute/unmute button. Those who did not manage were left behind.

In contrast: Generations of change agents have tried time and time again to explain and convince, using carrots, sticks and psychologically tuned arguments to convince people of doing things differently, just to fail most of the time.

One can always explain what should be done differently, providing detail on why and how. And most subjects will easily agree with that information, yet will not change their behavior. It is the actual action, after being performed and repeated, that forms a habit that will be carried out without external enforcement later.

The catch for change agents: If their primary job is not show and perform the very action they want their change subjects to learn (e.g. brave testing and iterating innovative, unfinished ideas with customers), they cannot credibly drive people to take this action on their own. Organizational theory is just information, not action.

A case example: Output orientation in a complex organizational environment

Excubate supported a large-scale cross-industry B2B software platform project that had undergone several reorganizations and still faced a lack of common internal understanding of project objectives and value creation goals, deliverables, and roles & responsibilities among the 100+ people working on the project. The stakeholder group was a highly diverse double-digit number of companieswith diverging, partly conflicting project objectives. Participants were unclear about their roles and involvement in creating outcomes. Too many people were involved in too many things, while staffed into roles they were not equipped to play. Quick operational alignment meetings, set up for 4 people, ballooned to 20 participants who were afraid of missing out. This gave rise to inefficiencies and political maneuvers, allowing only a limited amount of work to flow into actual value creation, i.e. development of software functionalities for an actual market need. Having started this project with a large-scale implementation of the SAFe (scaled agile) framework, supported by an Agile Expert Consultant, the leadership team quickly realized that this method-heavy, overstructured approach was not only directing too much attention of the team towards “learning and experiencing how agile works” and away from output creation, but it also confused people with the sheer number of roles, terms, release-train-frameworks, meeting types and the lack of pragmatism.

Subsequently, the SAFe approach was adjusted (not to say abandoned), and the teams were reorganized multiple times, up to the point where confusion was coupled by frustration, and the call for someone to help manage this organizational change (aka a “Change Manager”) got louder.

The approach we took to support change in this situation was not one of a classical Change Manager. A (very) short review of the situation and complication was helpful and done via a set of interviews across the organization. Although the situation was quite clear from the beginning, this helped create buy-in as well as clarify expectations within the client team. Then, however, other than merely asking questions and helping people reflect and come up with solutions for their issues themselves (information), our change role was to become an active part of the team and leverage real experience to effectively run and work in the project (action). Taking a very sober, rational and partially controversial stance vs. how things were done, we pushed for a different way of working (e.g. by prioritizing backlog items much more strongly based on customer value creation) to make a relevant difference. Senior members of the client team appreciated someone who voiced a clear, experience-based opinion and got their hands dirty to overcome project inertia.

To reduce complexity in the overall working mode and guide the client team through a simple, yet very effective results-creation path, we outlined four stepswhich we believe are generally helpful for delivering results in any, and especially in a complex, project environment:

1: Know what you are optimizing for

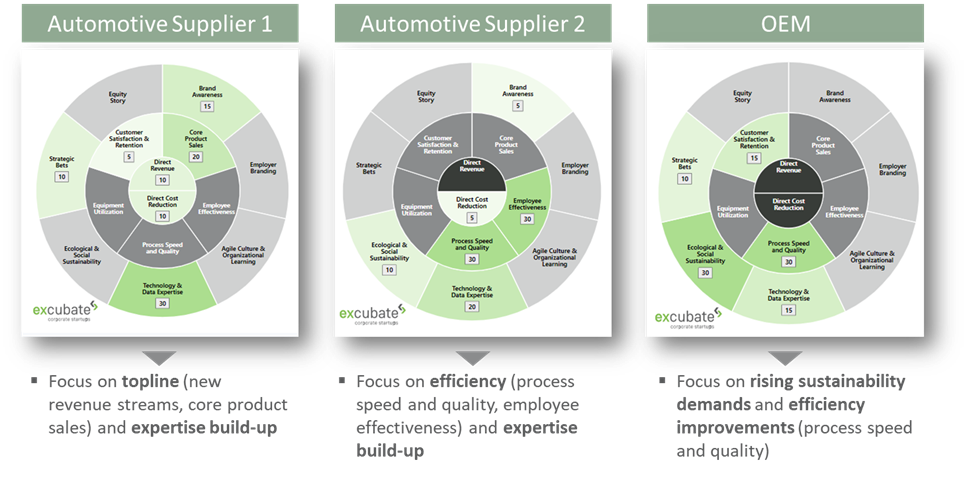

In large ecosystems, stakeholders always have diverging, sometimes conflicting objectives and agendas – and rarely position them openly. If there is no common ground on the question which problems are being solved for whom, it becomes imperative to enforce transparency on each stakeholder’s objectives and identify matches and conflicts. We use the Excubate Digital Value Canvas (https://www.excubate.de/digital-value-management/) to create this transparency for each stakeholder group, as well as – and perhaps even most importantly – for future customer groups. The value creation needs of the customers are always the smallest common denominator of what different stakeholders should be optimizing for. The example below shows value creation needs of different stakeholders in a mutual large project. It is interesting to see how two players of the same kind (automotive suppliers) aim to achieve very different things.

2: Define and prioritize deliverables to create that value

Value creation requirements must be linked to specific deliverables that help achieve that value. In software development terms, these are – among others – value-creating software functionalities. In other contexts, these could be projects to run or products to build. Sound prioritization – in a functionality backlog – must, among other criteria such as development effort, adhere to the defined value creation goals and have a clear rationale to build non-value creating features. Example: Building an automated customer onboarding functionality before any substantial number of customers is interested will create less value than some analytics functionality that a customer actually needs for their daily business and would be willing to pay for.

3: Devise specific, yet simple processes to create deliverables

Delivering on the prioritized goal must follow a clear approach. The term “process” is often despised in the agile community because it is perceived as old-school, and agile enthusiasts tend to have bad memories of corporate process fanatics. That is, however, a mistake. As much as the agile way rightly avoids waterfall methodologies and detailed, rigid process maps, it still requires some logic around the major steps to create outcomes (e.g. a simple 4-step process for value-driven prioritization of a backlog) to give people some guidance and minimize chaos. Prescribing the 4-5 major processes with 4-5 major steps each will be sufficient.

4: Make sure to have the right people play the right roles

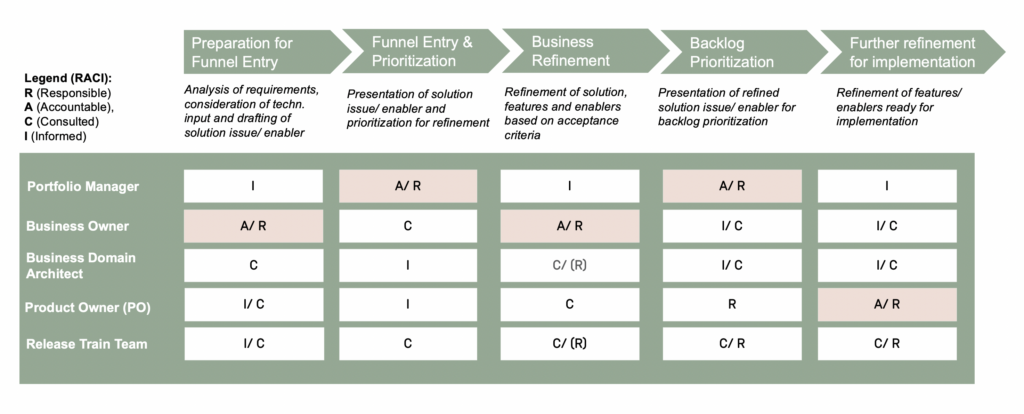

Only then, roles and responsibilities along these key processes can and must be defined, e.g. via a decision making framework such as RACI and a practical role description including a view on “when has this role done a good job.” Independent of the wealth of potential roles offered by the SAFe framework, this approach clarifies which roles (and, thus, capabilities) are actually needed to achieve the above and lays ground for staffing these roles with people that bring the right capabilities and capacities – see an example below.

If change is to have an effect, these four steps need to be taken sequentially, regardless of the starting point

While the above approach describes a certain blueprint, reality often differs and running projects may already have some elements of, say, steps 2 and 3, but nothing yet on step 1. And that’s ok. Our project example was not different. It is just important to close the gaps one by one, starting with step 1.

To achieve successful change management and get a struggling project/ organization back on track, we recommend three important behaviors for the person in charge:

1. Start with value, end with roles: Enforce a crystal-clear view on why something should be done, what should be done, how and by whom.

2. Take action (and don’t ride theory): Get involved & get your hands dirty; show, don’t tell how it’s done

3. Become part of the team: Nothing builds more credibility than becoming a part of the team you want to change. It is the doing that will make you an effective change agent.

So, the best change agent is not a change agent. Not someone who has only change in mind and change on their business card, but someone who actively and effectively helps drive towards desired outcomes and achieves organizational and behavior change on the way.

If you are interested in understanding Excubate’s viewpoint in more detail and drive some change with us, please reach out at innovate@excubate.de