Key takeaways:

- Traditional M&A DD approaches are too analysis-focused and stiff

- Outcome options are much broader (acquisition, cooperation, partnering)

- Decisions need a combination of data-driven and gut-driven input

- Team is just as important as figures

- You need to be attractive for the startup too – and make them trust that you will deliver

- Have a contingency plan in place to not lose ground when M&A fails

- Finally: Don’t take “nailing” the startup too literally – it needs to keep moving

What’s the deal?

In the dynamic world of digitalization, startups are scaling faster than ever and adapt even more quickly and agile to a fast-changing environment than corporates. Scaling globally within a few months is a clear desire of most startups and many – e.g. the communication tool Slack – show that it’s possible. This tempo pumps up the pressure for existing companies to not only innovate and scale new business themselves at higher speed, but also to consider partnering with and acquiring these fast-moving startups. The challenge, however, is not only their impressive multitude across all stages of development (up to 50 million new firms are founded globally each year, most of them vanish, of course). On top, these companies are changing and moving so quickly, that a newly identified startup may have doubled its size and changed its business model already 3 months later.

Still, and despite all the notions of agility and fast decision making, a clearly structured Due Diligence (DD) process is needed to find the right partner in the abundance of startups. However, in the dynamic startup environment, a classical DD approach may come to its limits due to its somewhat rigid and heavily fact-driven approach. Usually, a dedicated team follows a highly standardized process to evaluate a small number or even only one target. DD projects are opportunity-driven, following a “sniper approach,” as the corporate often already knows which company they want to acquire and there are not many options in any given market anyway. The Startup DD, in contrast, requires more of a “shotgun” approach at first to make sure no valid opportunity is missed out on. Further, the methodology needs to be agile, as startups in a fast-developing market are moving constantly and change happens within days.

In the startup space, it is also more difficult to collect relevant information than in a classical DD: either the needed input is not available or the startup’s management team does not have the time to provide or even create it, considering that reporting mechanisms, internal controlling, process and KPI frameworks may not have been established yet. Compounding the difficulty, the data is likely to be changing rapidly, anyway.

Timing is an essential driver for “fit”

The timing of the M&A is critical: Early-stage startups are more likely to rely on financial support, and being acquired may alleviate immediate financial needs. Logically, once the startup becomes larger, it either reaches a more stable scale and does not necessarily rely on an acquisition to keep growing, or the acquisition price increases substantially. Buying the company with only 75% certainty therefore may pay off more than waiting for another half a year to reach 95% certainty, as the acquisition price goes off the charts and other corporates jumped on the bandwagon.

The corporate should be very clear about the benefits the acquisition can provide to itself as well as the startup, e.g. providing access to more R&D or sales and marketing resources that accelerate the startup’s growth. The acquisition may give the startup a financial boost, optimized costs and/or increased revenues via new technologies or features built into own products; therefore, the timing of the acquisition should match the startup’s development stage – which, again, is tricky, given the fast development pace. Finally, scaling up from a prototype-stage with little volume to the corporate production volume of tens, often hundreds of thousands of units, is the toughest part and often the breaking point. Think of a car manufacturer with millions of units each year into whose production process a startup product needs to be embedded. In the DD phase, this aspect should be examined very closely.

Analysis is king, but agility is King Kong

Classic DDs follow a rather deterministic, structured and at times „technocratic“ approach, which is – rightly so – strongly data-driven to arrive at a specific valuation for the desired target. Yet, given the unpredictability of the moving target, acquiring a startup may need an entrepreneurial decision – and hence a leap of faith – on the corporate side. A too analysis-driven approach may provide a false feeling of predictability that in fact isn’t really there and may put the corporate into analysis paralysis.

The Excubate methodology builds upon a thorough understanding of the corporate and the startup worlds along with their respective business models to balance the characteristics of a dynamic environment with a data- and fact-based reliable model.

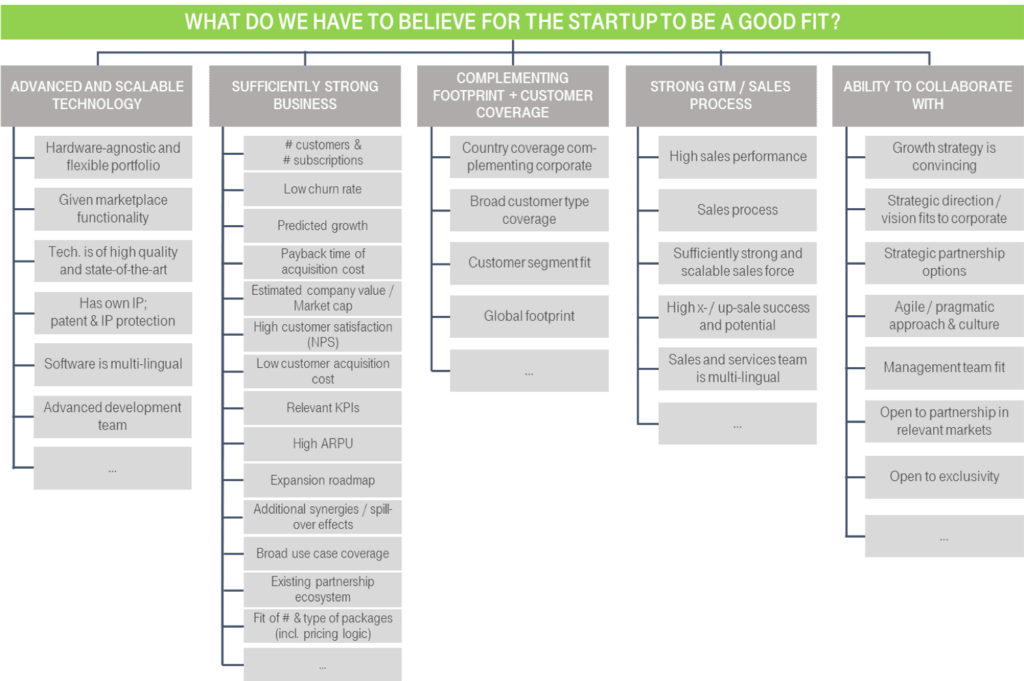

To provide an objective and pragmatic comparison of different startups, we map the entrepreneurial objectives of the corporate with regards to where they want to play (products, customers, markets) and how they want to win (processes, decision logic, incentives, capabilities, organization) with the startups’ ability to complement or counteract these. Based on this, we build an assertion logic that clearly outlines what the corporate is looking for. We typically derive a specific assertion tree similar to the example below.

For each hypothesis, criteria are defined that need to be fulfilled to prove the hypothesis. Based on this, the criteria are weighted on a scale from 0 – 3 (0 = “just informative”, 1 = “less important”, 3 = “very important”). This helps identify key criteria and potential show-stoppers.

Based on this catalogue, each startup is evaluated along the criteria on a scale from 0 – 100% for the level at which they deliver on the criteria. To assess this objectively while staying pragmatic, the evaluation needs to be as data-driven as possible, but at the same time as entrepreneurial as needed. This is an iterative approach to evaluate the startup fit and both, the criteria weighting and the startup evaluation, need to be challenged and adapted constantly with every new learning. This way, we can “force-rank” all relevant startups against each other and a ranking can be maintained throughout the Startup DD project, based on the current status of analysis.

Excubate approach

Studies have shown that more than half of all M&A deals fail. Key reasons may be that the valuation has been too high in relation to the value created, the acquisition’s synergies had not been carved out enough or a cultural misfit led to failure. This problem can be illustrated by the well-known cases of failed large mergers, and it is becoming increasingly prevalent among the mergers between corporates and startups. To avoid this, we typically follow 3 steps to complete a successful startup DD.

1) Get clarity on the corporate’s strategic and tactical goals (1 – 2 weeks)

The Startup DD starts in a very early phase when there are still many uncertainties: What are the corporate’s strategic goals with a new type of business and technology? Which type of collaboration is the best solution? An acquisition is a tactic to execute the corporate’s strategy for a business vertical, and not a strategy in itself. This means, prior to the process of the startup evaluation, all other alternatives should have been considered, i.e. cooperation, licensing, building in-house, partnering or co-investing. Also, in many cases, the objectives of a corporate are not fully clear in the first place, especially in the field of digitalization and new business development. So even this first phase may end up as a learning experience for the corporate.

The corporate may be kick-starting a certain business, trying to secure a basic technology or patent for further innovations or just trying to prevent disruptive competition. Software maker Atlassian, for example, recently acquired Trello, a startup re-inventing Kanban-based project management and attacking the corporate’s JIRA from below. Atlassian acquires two startups per year, not only to leverage their technology, but to bring their startup culture to the company – therefore one of the prerequisites is that the founders stay in the startups after the acquisition.

Based on the defined strategy and tactical objectives, the specific assets, processes and capabilities, the corporate can and wants to inject need for clarity. Will the corporate bring in customer access, sales/service power, technology, brand? And how should these be combined with a startup in a partnership or acquisition?

Important cornerstones need to be pre-defined to keep the number of potential startups manageable, e.g. their industry focus, minimum revenue, footprint or ownership model. Furthermore, it is helpful to think about the company size upfront: Should the startup be already established and generate revenue or should it still be in an early phase to leverage the corporate’s development capacities? These cornerstones are the blueprint for the detailed criteria catalogue described above.

Besides the internal perspective on the strategy, the market environment is equally important to understand – and naturally also a very dynamic one if we talk about the startup space and rapidly developing markets (think of markets to trade 3D printing capacities, that are just emerging today). Interviews with experts are crucial to derive strategic perspectives and conclusions beyond what is available in research reports.

2) Identify and evaluate relevant startups (4 – 6 weeks)

Based on pre-defined cornerstones, a long list of potential startups is created. Researching market studies is a good starting point to get an overview of relevant players. National and international startup data bases, such as Spotfolio and Crunchbase, help to collect further relevant information and KPIs. Existing contacts, the personal startup and founder network should be leveraged to complete the picture. The goal should be to find as many relevant startups as possible to have a wide choice (that then should be narrowed down quickly and rigorously) – the number of interesting companies, however, highly varies with the entry barriers of the respective industry.

Along with the iterative development of the criteria catalogue – and therefore the definition of key criteria and show-stoppers – the long list can be shortened down piece by piece. We recommend to get in touch informally with the most interesting startups as soon as possible, by visiting startup conferences, panel discussions or directly setting up phone calls. In these first discussions, usually reasons for immediate rejection show up, e.g. that the management team is unable or unwilling to enter discussions, new show-stoppers are discovered or the startup simply is not ready yet to discuss potential collaboration models. After each interview, the criteria catalogue is updated, and the evaluation logic is refined, cutting down the list to 5 – 8 potential acquisition targets.

There is an important learning for the corporate here, which is that it needs to be sufficiently attractive to the startup as well. We see it all too often that startups, while seeing tremendous value in cooperating with corporates, refrain from even entering discussions because the respective corporate has a history of proposing and promising, but then not delivering. Having a reputation of actually moving quickly and pragmatically helps a corporate tremendously in gaining credibility with startups.

With the remaining startups, workshops are conducted to get information that cannot be collected through desk research, e.g. their F&E focus and budget, growth strategy, soft factors like company culture, and sensitive KPIs. Focus should be on the high-ranked criteria, e.g. relevant technology features or the maturity and scalability of the sales process, to create a sufficient assessment. Discussions on first potential collaboration models show with which constellation the corporate’s assets can be leveraged most effectively. After the first round of workshops it is usually quite clear which ones are the top 3–4 companies to start a more detailed discussion on a potential joint growth strategy.

Those discussions may also lead to a change of the strategic direction, e.g. if the corporate detects unforeseen synergies between two startups and decides to acquire both. Another outcome may be that starting with a partnership and acquiring later is the better choice, based on the startup’s potential in relation to its state of development and therefore the risk that the corporate is willing – or not willing – to take.

To get an external perspective on each company, which is the most important aspect of the customer-centric startup world and its methodologies, it is an imperative to conduct customer interviews. In a 15–30 minute, rather hands-on and pragmatic call, we discuss aspects like sales process, customer satisfaction, product and service request handling to cross-check the information provided by the startup. Furthermore, scanning relevant online forums and portals to analyze reviews and customer feedback completes the external perspective.

At this point we typically arrive at the prime candidate that has shown interest in an acquisition and opens its books for further and final investigation. The deep dive business model DD needs to be conducted, i.e. developing a scenario plan for value creation (case calculation).

Besides that, a financial DD and a legal DD will of course be completed as well. Both, however, should exhibit a similarly pragmatic approach as the process thus far. Otherwise there will still be a substantial risk of stalling. This may mean that both parties involved on the financial and legal side run a simplified and shortened process, ensuring that “bet-the-farm”-risks are minimized and major show-stoppers identified. It would also pay off to allocate more progressive finance and legal experts to these DDs than it would typically be the case in traditional M&A.

3) Execute acquisition and link up the startup with the corporate ecosystem

This is of course the trickiest step. And there are plenty of well-known insights around mid- to long-term incentivation of the startup team to stay with the company (earn out) as well as a thought-through communication approaches for both the corporate and the startup to avoid culture clash. We don’t want to further elaborate on these here, but focus on finding an actually working approach for integrating processes and organizations, as we perceive these to be the tough part and actual enabler of culture integration and ultimately success of the whole endeavor.

To make the acquisition actually work on that operational level, an appropriate (not too little, not too much) integration needs to happen. Based on the insights from earlier DD phases, the areas and processes to integrate vs. to leave alone need to be specified and scoped out. For example, if it’s crucial to have an integrated go-to-market to leverage the corporate sales power and customer access for the startups products, an integrated sales process and team needs to be designed. R&D and production could and maybe even should remain fully separate for optimal performance. If the startup product, however, needs to be integrated into the corporate supply chain and scaled up to thousands of units, this integration needs to be put in focus.

Since the cooperation/ M&A of a startup is rarely just a financial investment approach, but has a strategic objective, we always suggest that our corporate clients have a contingency plan in place for the not unlikely case of the acquisition not working out. A failed M&A approach could easily eat up months of valuable time to build a new capability or business and put the corporate in the back seat on the market. The alternative should always be building the business internally with sufficient funding and firepower, that would otherwise have gone into the acquisition.